Focus on the field. Always

Asbjørn Eidhammer is former ambassador to Malawi, and previously head of the Evaluation Department at Norad. In this evaluation view, he expands on his presentation from the panel debate at the launch of the report Evaluation of Organisational Aspects of Norwegian Aid Administration.

An evaluation report from the consultancy company Menon finds that the focus of Norwegian development cooperation has shifted from a country level to global efforts. The authors use an integration-response framework, with local responsiveness opposed to global integration, to illustrate this development, which is also linked to a trend towards more thematic concentration in Norwegian aid. The thematic emphasis on climate mitigation, health and education has contributed to a strong increase in Norwegian funding through multilateral organisations and global funds. The percentage of aid through embassies has been drastically reduced in the total of Norwegian aid. This has resulted in a remarkable centralisation.

In the report the consultants expect these trends to continue in the future. I am not so sure. Development policies seldom follows a straight line, sometimes they even end up in full circle. I am a multilateralist, but in no way do I see blues skies ahead for the multilateral system. Globally, national interests seem to be taking over, as is also acknowledged in the report. In my view, an ideal situation would be that the fight against poverty and inequalities would be a common responsibility, with efficient global structures and organisations to carry it out. That would be justice. But we are not there, far from it, and the world may be moving in the wrong direction.

Other factors do not favour increased global integration. The trend towards global channels is accompanied by an increasing demand for results and more comprehensive planning, and reporting systems for results are being introduced. An problem, however, is the difficulties in documenting the impact of funding through global arrangements. In many cases, it is even hard to find out what Norwegian funds have been used for. But the public demand results, and will do so increasingly as our funding through global arrangement increases.

Another finding in the evaluation raises concerns for me. When Norwegian-funded programmes do not succeed, a reason is very often the lack of knowledge and understanding of the local context and developments. This means that in order to improve our development activities we need to strengthen our country presence, and build capacity and knowledge in our staff, in a more long-term manner than today.

The embassies find the lack of strategic support and expertise on development issues in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs a problem. I agree with the argument in the report that improved access to information through digital technology may strengthen headquarters’ ability to gather information and strengthen analysis. Nevertheless, it is easy to underestimate the challenges of reliable data, in particular in low-income countries and countries in conflict. As Morten Jerven has shown, we know less than we think we know, and the numbers we use are very often very uncertain. Besides, it is important to have understanding, not only to count. Staff on the ground are in a unique position to understand. Knowledge at home can never substitute knowledge in the field.

To deal with the lack of competency in the Ministry we must see development as a policy area of its own, like climate policy or international health policy. The administration at headquarters should be structured accordingly. The efforts of a structural integration of foreign policy and development aid has gone too far, resulting in a dilution of knowledge and competency. Expertise on development must be strengthened and protected. The experience from climate and international health policies show that policy integration may work well without full structural integration.

Money counts. Even if competent diplomats may be able to influence partner governments when direct aid diminishes, this will be the exceptions. The same applies in development cooperation as in other fields. If you do not have financial weight as a development actor you are not invited to the table. If Norway is to play an important role in the countries where we are present, we need to have substantial bilateral financing.

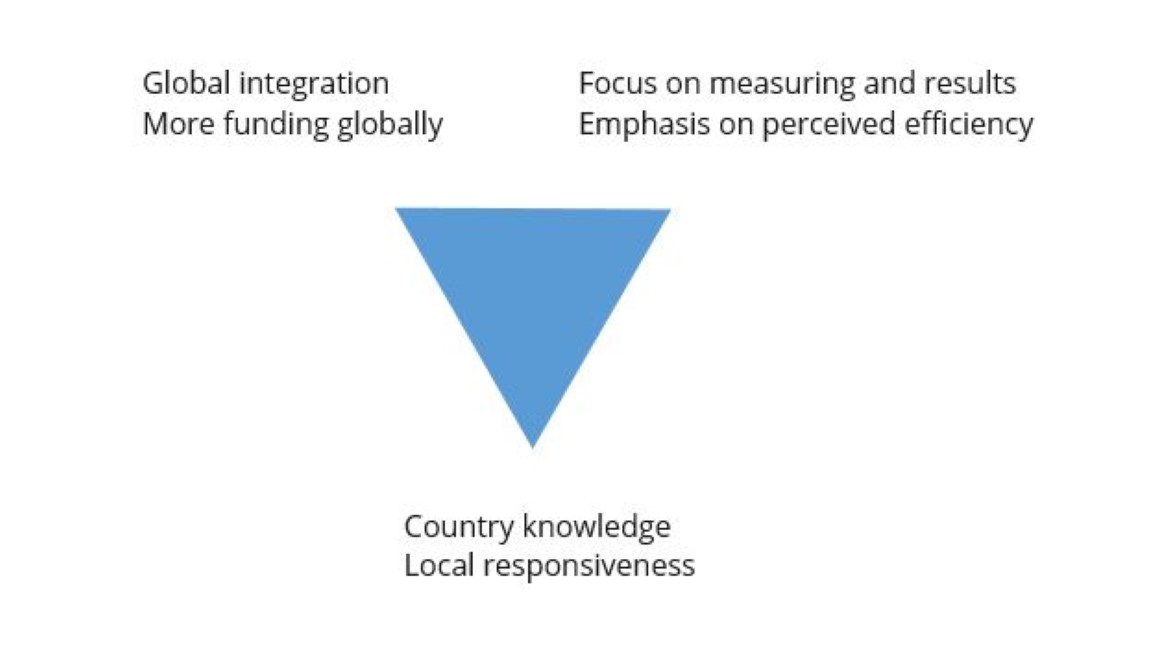

The strategic issues of organisation and channelling can be presented as a triangle. In one corner is global integration. In another is knowledge of the local situation and in the third corner is result orientation and perceived efficiency. (see figure below)

If the main emphasis is focused on global integration and measuring results, with less funding going bilaterally, we are heading for trouble. Firstly, the two corners on top will contradict each other. The more funding through global arrangements, the less we will know about the results of our efforts. Secondly, should our presence at country level weaken, we will have less competency to influence and successfully demand results from our global partners.

The sustainable development goals will guide our development policy for the next 12 years. Reports from the Brooking Institution in Washington and others show that 30-40 low-income countries and countries in conflict and crises will need massive aid if they are even to come close to achieving the goals. Most of these countries are in Africa. In the extraordinary efforts needed, Norway should contribute with the means and through the channels that are available to us. There is no evidence that multilateral organisations or global funds provide more efficient aid than direct Norwegian support does. The administrative costs do not disappear because we leave our money with the multilaterals.

In the efforts to mobilise funds globally, like in the Global Financing Facility for maternal and child health, a focus on the field approach should be accommodated. Whichever channels we choose, the impact, or lack thereof, will be measured in the field. A lot has been achieved through global efforts over the last decades. However, when it comes to what is most important, to contribute to building capacity that enable partner countries to take charge of their own development, the results are discouraging. Of the 32 countries with the lowest capacity in the world, 26 saw their capacity being reduced between 1996 and 2012. There is a need to rethink, a more pragmatic and problem-centred approach with greater flexibility is required. A strong Norwegian presence in the countries we engage in, with sufficient funds, is vital also in the 2020s.